The Awesome Science of Apples at Mercier Orchards

By Laura Mast

“There’s a lot more science than people realize. People think, you go out there, you dig a hole, you plant a tree and pick it. There’s a lot more.” David Lillard, orchard manager at Mercier Orchards, leans back in his chair and smiles good-naturedly at me and Ian Flom, Mercier’s brewmaster. Flom adds, “I grew up local, in this area. I knew Mercier’s was an apple farm, but I didn’t realize how extensive the process was until I actually became an employee here.”

“There’s a lot more science than people realize. People think, you go out there, you dig a hole, you plant a tree and pick it.”

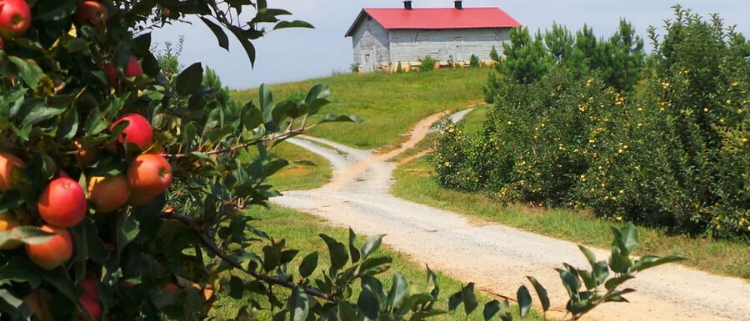

In its 75 years of operation, Mercier Orchards has grown to over 300 acres with over 100 thousand fruit trees. Nestled in the North Georgia Mountains, it’s blessed by temperate conditions perfect for growing apples: moderate summers, cold winters, and high humidity. Lillard tells me they get 60” of rain every year.

These features, though, also present dangers. Moisture is also great for pests, and an early frost in the spring could kill the budding fruit. Keeping these many trees – and the new trees they buy each season- healthy and hearty, takes a careful eye, hard work, and of course: science.

A flood of pheromones, and a blanket made of ice

Lillard has a few tricks up his sleeve to handle pests and frost.

“There’s just no way I can fight that disease cycle organically in this neck of the woods,” says Lillard. But instead of using pesticides every year, they rotate in four-year cycles. They’ll do a round of regular pesticides in one year, and then for the other three, they do an organic treatment focusing on the two most prevalent pests: the oriental fruit moth and the coddling moth.

Each spring, orchard laborers go into the fields and hang lures from the branches of every other tree. These lures, which look like bread ties, are soaked in insect pheromones, and flood the orchard with scent for the next 90 days. These confuse the male insects, who use the smell to track female insects. As a result, the males are unable to locate and breed with female insects.

If insects are a long-term issue, weather is a short term one. “I spent a lot of time, effort and money getting a crop to a certain point and I could lose everything in five seconds if Mother Nature decides to take from us. You have to be pretty zen to work in this industry,” says Lillard.

“You have to be pretty zen to work in this industry.”

If the temperatures are forecasted to drop so much that the apple buds are in danger, Lillard turns on an overhead irrigation system. This system mists water vapor over all the trees. As the water condenses on the trees, it goes from a gas to a liquid. This is an exothermic reaction, meaning the water releases heat onto the buds, keeping them warm.

Keeping trees healthy is important because if “a tree gets sick,” says Lillard, “that’s it. There’s no cure- only prevention.”

One particular strategy for keeping trees healthy is, unsurprisingly, starting out with healthy trees.

Where do baby trees come from?

Well, in the case of apple trees, it’s not quite what you think. Apple trees are not “true to seed:” that is, if you were to take the seeds from your Red Delicious apple at lunch and plant them, and grow them into a tree, the fruit from that tree would not produce Red Delicious apples. “They might taste like cork, but it will be an apple,” laughs Lillard.

Ninety-nine percent of all apple trees in the US are produced using a technique called grafting. A grafted apple tree consists of two parts: the rootstock, which includes the roots and the base of what will be the trunk of the tree, and the scion, which is the stem. A wedge is cut out of the rootstock, and the base of the scion is cut into a wedge. The two ends are jig-sawed together and wrapped until they heal together. You can see this junction in a young tree as a distinct bulge in the trunk a few inches above the ground.

While it’s easy to see the role of the scion- it creates the apple varietal you want! – the role of the rootstock is a little more complex. The rootstock controls the size of the tree, the age when the scion will start to produce fruit, how the tree responds to adverse conditions like weather, insects, and diseases, and more.

Most orchards, including Mercier, order their trees from nurseries. It takes three to four years to grow the rootstock, and then several more years before the tree is ready to bear fruit.

Predicting the future

Image credit: Select Georgia

“I’m 5, 6, 7 years down the road before a tree is going to produce so I got to make sure I get what you want in seven years,” says Lillard. To choose new apple varieties, he and his team will go to horticulture shows and taste test: “We sit down and we’ll sample 100 apples, and we’ll figure out what they taste like. We learn how it’s been growing in the nursery, some other characteristics and then we’ll say hey, that’s a good one. We’ll plant that one and we’ll try that one.”

“I’m 5, 6, 7 years down the road before a tree is going to produce so I got to make sure I get what you want in seven years.”

After working in the orchard for twenty years, Lillard knows his trees: where you could get out fancy scientific gadgets to measure color and sugar, he just uses his hard-earned experience.

“There’s not a lot to it,” says Lillard. “If I know it’s that time of year, so if I know that reds come in at the beginning of September, I’m looking at Red. Do they have enough color? Are the seeds black? Do they taste good?”

You can always try taste-testing yourself: Mercier Orchards offers U-Pick weekends through the summer through the fall, during prime harvest seasons, complete with tractor rides throughout the farm. Put it in your calendar! “If I like them, and they’re ready to go, well, that means you’re gonna like them.”

Can one bad apple really spoil the bunch?

Assortment of apples from Mercier Orchards

Turns out, yes, and here’s where the cool science comes in with harvesting: storing the apples. You may have noticed that just about any time of year, you can buy apples, as if they were just freshly picked yesterday. This is the result of treatment with 1-methylcyclopropene, or 1-MCP.

As fruits ripen, they release a natural plant hormone called ethylene. This gas prompts the plant to ripen even further: the fruit becomes softer and sweeter, until your forgotten apples are mealy and soft. The ethylene binds to ethylene-specific receptors in the apple skin, which fit together just like a jigsaw puzzle.

1-MCP looks very similar to ethylene, and it can trick the receptors into letting it bind in ethylene’s spot. 1-MCP treatment fills all the receptors for ethylene with 1-MCP instead, effectively hitting pause on ripening.

This allows growers to ship out fresh fruit all year round, so you can make your own apple pie any time of year (or, pick up your own or order from their store any time!).

Come for the apples, stay for the (hard) cider

The Tasting Room at Mercier Orchards

At Mercier Orchards, the apples are divided: of course, there’s fruit for sale in the marketplace, and a good portion goes to the kitchen for pies, fried pies (you haven’t lived until you’ve had one, they sell over one million annually), breads, jams, preserves, relishes, butters and all kinds of sauces, and more. But the rest goes to cider, both hard and regular. This is Ian Flom’s territory. As the brewmaster, he’s led the production of hard cider in particular; regular cider has been an orchard staple for decades.

“When I started making cider, it was just a way to get rid of fruit that I couldn’t sell in the market. Now, I set aside blocks of trees purposely as cider fruit,” says Lillard. This has allowed Flom and his team to experiment with a lot of different flavors. Flom says the most variability in regular and hard cider flavors come from the apples: with 10,000 varieties of apples, it’s easy to see how.

The main things to consider are sugar content and acidity, says Flom. “You’re not going to have the same acidity level in a Red Delicious versus a Mutzu or a Granny Smith, right? Well, just that difference in the acidity can change your flavor profile of your juice. If you were to heavy on the reds and get, let’s say, one part green apple, and then you’re not gonna have the same tartness after fermentation.”

Fermentation is done very similarly to wine: yeast is added to the apple juice mixture, and it consumes sugars, producing alcohol. Fermentation only takes about two weeks; in fact, for a 500 gallon batch of hard cider, going from apples to bottle takes only 18 days. But it’s after fermentation that the fun begins.

Experimenting with Flavor

Flom tends to experiment with small batches (3.5 gallons) at home before bringing his ideas to work. He says the open-minded and passionate attitude of the team has led to some fun discoveries.

The Just Peachy recipe, a hard sweet peach cider, transformed along this vein. “I remember, David asked me ‘why don’t we do something hot?’ Why not? And then you know, through some trial and error, we end up with the Jalapeacho, which is one of our top sellers.”

Another example is the Gone With The Ginger, a sweet hard cider that was born after Flom had been cooking at home. “What if I put some ginger in it? What if I cut it up first, what if I roast it, cook it? So it’s a little trial and error.”

Regular cider doesn’t require nearly as many steps. After the apples are juiced, the juice has to be pasteurized. At Mercier Orchards, they use two different pasteurization methods. The first process, full pasteurization, heats the juice to 180 degrees, yielding a cider that’s shelf-stable for up to two years. Flash pasteurization, however, only heats the juice very quickly to 161 degrees for a matter of seconds. The flash pasteurized juice retains more flavor but doesn’t last as long.

Modern agricultural science at Mercier Orchards

Image credit: Select Georgia

Tim Mercier, CEO of Mercier Orchards, has said he believes the company’s willingness to learn, adapt and change are their most important assets, something that Lillard and Flom strongly support.

Years ago, the farm was only open from September to December; now, 12 months a year you can head to the farm and do so much more than buy apples. Beyond the bakery, the café, the winery, and the marketplace, you can also take a cooking class, do a tasting, take a tractor tour with a guide, or get out in the fields and pick fruit yourself. Every year brings new varieties of apples, and they’ve expanded to peaches, blueberries, blackberries, strawberries, and nectarines as well.

So load up your family, and take them up to Mercier Orchards for a day outside, with a cup of hot cider, a fried pie, and see this family farm do modern agricultural science for yourself.

Thank you so much to David Lillard, Ian Flom, and everyone at Mercier Orchards for taking us through the science of apple growing! To keep up with Mercier Orchards, follow them on Facebook and Instagram. Check out their website for the most up to date information (and to place any orders!): https://www.mercier-orchards.com/

Follow Science ATL on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for more Awesome Science of Everyday Life features and other science updates!