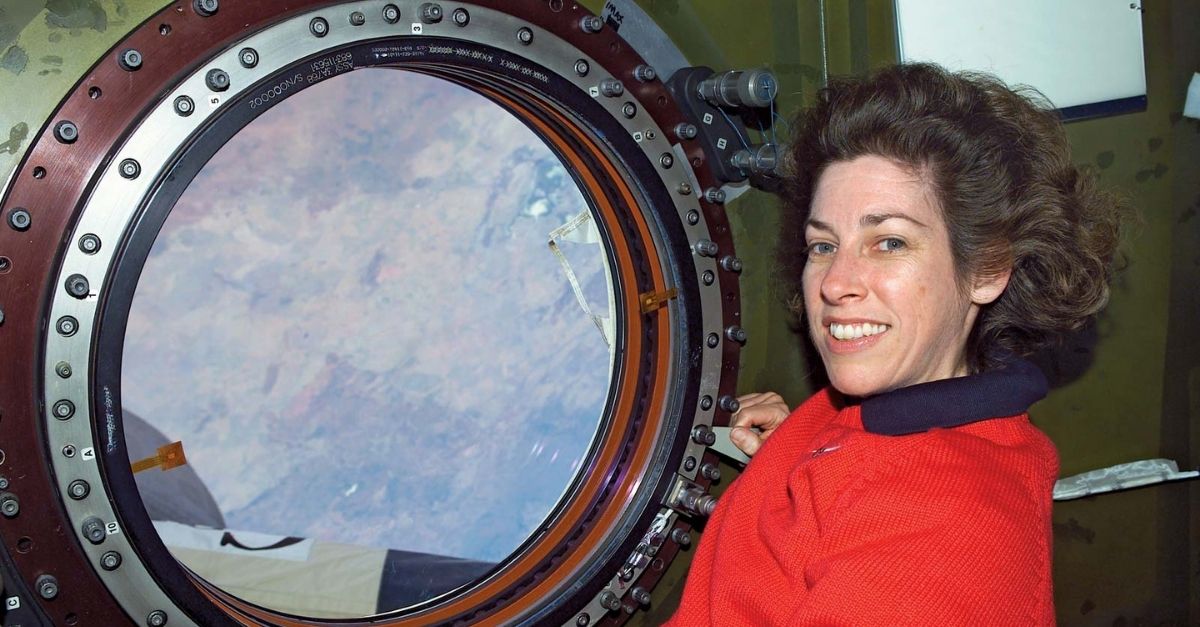

Changing the Face of Medicine: Jennifer Giroux

Over the last nine months, we have grown very accustomed to hearing from Dr. Anthony Fauci and other public health leaders who help us better understand COVID-19 and the threats it poses to our health and the health of our communities, nation, and the world. Many of these voices are those of epidemiologists, often referred to as Disease Detectives, who search for the cause of diseases, determine who is at risk, develop plans to stop or control the spread, and try to prevent it from happening in the future.

Captain Jennifer Giroux, a member of the Rosebud Sioux tribe, is a medical epidemiologist who focuses on preventing disease outbreaks among Indigenous populations in the Great Plains Regional Office of Indian Health Services, a division of the US Department of Human and Health Services. These regional offices provide healthcare to all tribal nations and communities in designated states.

Giroux moved frequently while growing up in South Dakota and Montana and never imagined she would become a doctor. In a fantastic online exhibition “Changing the Face of Medicine,” created by the National Library of Medicine, we learn that her inspiration to become a doctor emerged from traveling in developing countries where she realized her privilege as an American when compared to many women around the world. She was determined to take advantage of her opportunities and then work in Indigenous American communities where resources and services are often lacking, especially in medicine and public health.

Early in her career, Captain Giroux recognized the need for collaboration among medical and public health professionals around health crisis responses as well as the need for culturally-relevant communication and education for Indigenous communities. In other words, when professionals want to provide information or medical support to tribes, it is important to integrate relevant cultural references to create trust and a sense of safety. This is a reason many Indigenous people, like Captain Giroux, put their education and training to work in tribal communities, to ensure people will not suffer because of misunderstandings or prejudices.

Her current work in the Great Plains is part of a larger network of Tribal Epidemiology Centers that work together to reduce public health disparities and improve the health of Indigenous Americans across the country. Captain Giroux and her Tribal Epidemiology Center colleagues around the country have been working tenaciously to ensure tribal communities receive the necessary education, surveillance, prevention supplies, and information to stay safe during the pandemic.